There Must Be Something in the Water

By Paul Jhon Diezon

For Context

The Sustainable Development Living Lab is one of the courses required for our Master in SusDev program. This course lets us conduct an independent observation of a certain locality, including (depending on the situation) sampling of certain biophysical conditions and interviewing key stakeholders about certain economic and social aspects. The main objective is to craft a development plan with and for the locality. Every year, students from our program visit different communities in developing countries. For our cohort this year, a community-based tourism area in Northern Vietnam hosted us with partners form the Vietnam National University guiding the group in the whole duration of the excursion. I was in the group tasked to assess the water quality of streams in the said area.

What We Did

In our two-week stay in Hoa Binh, Vietnam, we were able to do a brief assessment of the streams that flow along forests, villages, and agricultural lands. Our team of five were accompanied and guided by three mentors, Mario, Hannes, Hoa and Son, with Phuc being our Vietnamese volunteer (could pass as a mentor too!) It is the first ever Living Lab organized in Vietnam so we are quite excited to see what’s in the waters.

Using various equipment, we gathered data about the abiotic factors in these water bodies. For instance, we have collected data for nutrient concentrations particularly that of phosphorous and nitrogen as these nutrients are important drivers of potential pollution in water bodies. These may affect the primary productivity in the area and may dictate eutrophication when excessive amounts of these are recorded. Dissolved oxygen is also recorded to give us an overview of how the streams are capable of supporting life. The striking trends were found among the streams we have studied. The most worrisome observation we have seen is the evident plastic pollution in some streams near residential areas, which were found floating through the current or washed along the banks.

This is how we do our sampling. We use nets to catch the macroinvertebrates and use tweezers and pipettes to put them in an alcohol-filled vial for preservation © SUSDEV

Perhaps the biggest challenge for the team was the identification of various macroinvertebrate larvae collected in 35 sampling locations in four different villages. In the Mai Chau village, a striking trend was found among streams near residential areas, streams found in agricultural areas, and streams that are classified as natural. Diversity, abundance, and evenness was greatest in areas that are more natural. A decrease in diversity and abundance was found in streams near rice fields, while the least diversity and abundance was found in streams which passed through residential areas, which may be attributed to household activities and to some extent, may be correlated to tourism activities too. Biodiversity is an integral component in identifying how healthy the streams are. Greater biodiversity may entail greater community resilience and is dependent on healthier water sources. Cleaner streams allow for specialist species to thrive better, as these species are usually less tolerant when it comes to pollution and other stresses. In contrast, generalist species thrive on less clean water. To add, natural streams far from agricultural and residential areas were found to have more specialist or indicator species of clean waters. The families of ephemeropterans (family of mayflies), plecopterans (family of stonefiles), and trichopterans (family of caddisflies) are great indicators of cleanliness and are used in various indices all over the globe as a criterion to know when a body of water is clean or not.

Moreover, we have collected some species not even published in the monitoring scheme used here in Vietnam. It is then important to continue sampling these areas again and maybe this will be an opportunity for the next living lab team to explore! Some of these macroinvertebrate families are not even in the dichotomous keys used in the country which is quite an exciting find and even more exciting to monitor!

Onto the Favorite Part

One of the highlights of our Living Lab adventures is working with the kids in the village watching us sample the streams nearby. We let them gather samples with us and it is not surprising that they were of big help! Of course, they know more about the streams than we do. We tried to explain what we are doing, and they followed us until the last sampling point of the day while chatting about lots of things.

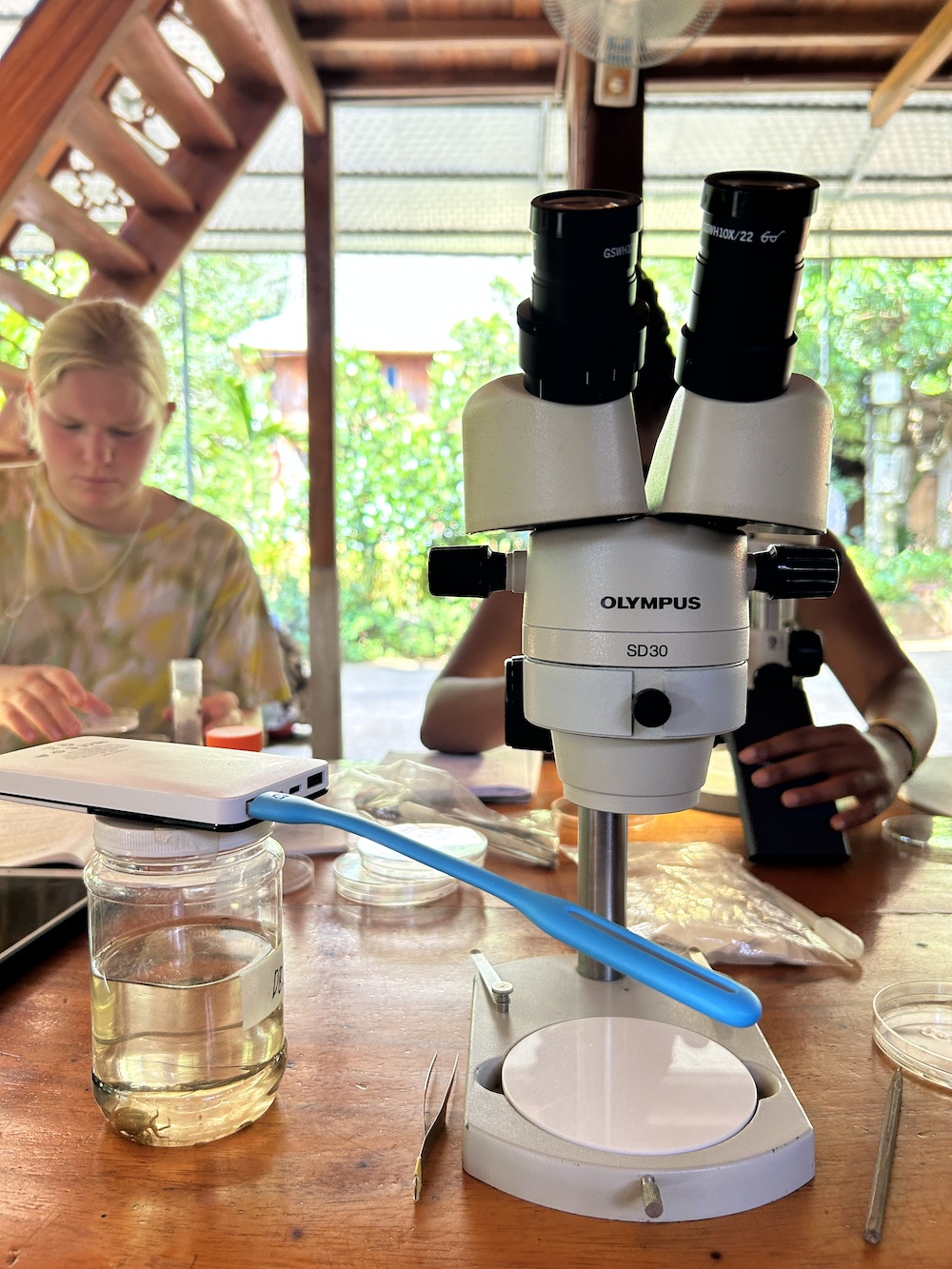

A dissecting microscope and a little added light are all we need for a makeshift lab to work! © SUSDEV

This experience made me evaluate my plans in the future as it has inspired me to look more into the importance of co-producing knowledge with the community which is not (yet) a norm in the natural sciences. This is where my interest in citizen science came to develop. This new concept enjoins the public in recording scientific observations which contributes to a larger database which can be better utilized in monitoring the water quality in the future. Not only does it contribute to knowledge creation, but it could also potentially spark curiosity which may lead to better safeguarding of their natural resources. And with the advent of smartphone use, it is now faster to connect and collate data in any part of the globe. Not only that, but findings from these observations can also indeed guide the community in making informed decisions about their community’s ecology and may be linked to various governance strategies to fit larger management scales.

It is amazing what science brings us, but the bigger question is do we bring them to the people who need the information the most? Are we doing enough to extract the maximum potential of these discoveries? The best thing to abridge this gap is doing it with the community, encouraging them to do it independently in the future, and more importantly, learning from their practices as well.

In our trip, I realized that we were not just there to study what the water quality is like in Northern Vietnam. We were there to also study the various factors that come into play in these community-based tourism programs like their governance, gender-related topics, biodiversity, and the way these factors affect each other.

On a more personal note, the trip made me think of the things I wanted to do in the future. As such, I made the decision to explore citizen science and its potentials in my portfolio and decided to make it a personal advocacy when I come back to the Philippines.

So yeah, this trip was more than just knowing what’s in the water. The experience was much deeper than that.