By Jan Drela

Waste picker in action © Janne

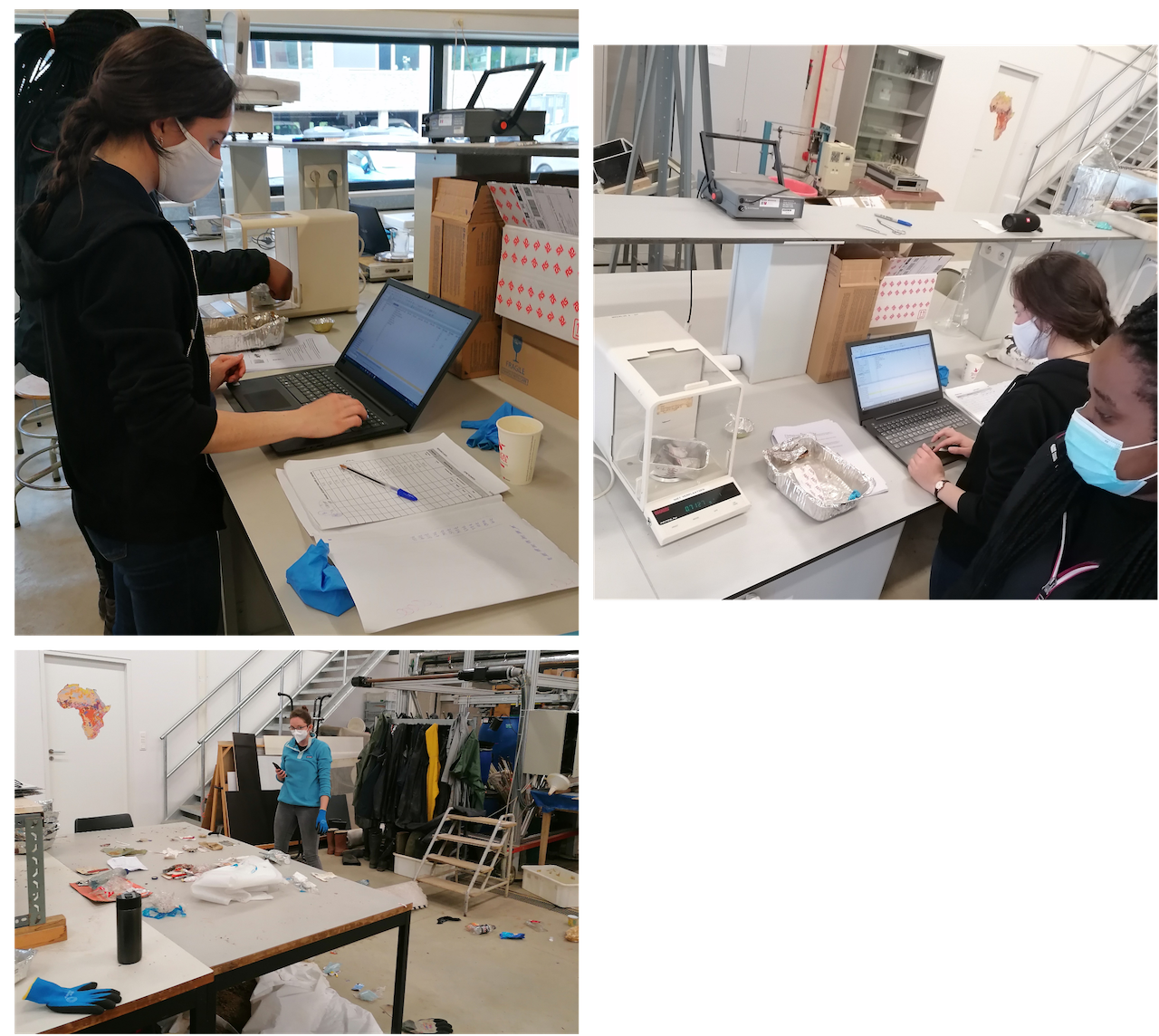

A good teamwork brings good results

© Janne

Found waste consisted mainly of plastic packaging, bottles, soda and beer cans, paper and, of course, face masks as well © Janne

Classifying, counting and weighing waste in the lab

© Janne

After writing our first development plan for South Africa, the Ndumo area, we had to adjust it to quite a different context and environment. Indeed, the waste management, situation and challenges in Belgium are very different from those in South Africa, particularly in the researched rural area. In South Africa waste management in (poor) rural areas, like the Ndumo region, is predominantly informal and waste, including solid municipal waste, is mainly dumbed, landfilled or burnt. Moreover, Leuven is an urban area with a developed infrastructure and waste facilities and services, while the Ndumo region is rural with underdeveloped and often missing infrastructure, facilities and services. Given the good waste management system in Leuven and our own experience from living in and walking and biking through the city, we assumed we would not find a significant amount of waste. Therefore, it seemed that this type of mapping research would not make a lot of sense in this context. However, during the fieldwork we were actually surprised how much waste we found. Things are not always as they appeared at first sight or from a distance. As the saying goes, one who seeks finds.

It is 8:30 in the morning. We are ready to venture out into the streets, parks and zones of Leuven. We gather at the GEO institute, collect all the necessary equipment and bike to the first zone of the day. Normally, we need to cover three zones per day. The group is divided into pairs and each pair scouts one subzone. We spend up to one and a half hour in one zone collecting, noting down all the relevant information, taking pics and georeferencing the waste with a GPS device. We notice that the very city centrum is cleaner than the other residential and built-up areas. This is quite logical since the centrum is the most representative part of the city which attracts the most tourists and visitors. In fact, the centrum is cleaned up daily. The biggest problem in the centrum are cigarette butts and food packaging from takeaways. This type of waste, if littered intentionally, points to irresponsible and careless consumer behaviour and logic of consuming and throwing away not caring anymore what the consequences of such behaviour are. If we are what we eat, then we are also what we throw away. In other words, waste and how we handle it reveal not only what we eat, but also something about us. This applies to cigarette butts as well, but they are a bit different. This type of waste, also due to its small size, is not perhaps really considered by many to be ‘real waste’, and so is more easily littered than bigger, less degradable waste. Moreover, it seems safer to throw a cigarette butt in the sewer or on the pavement than in the garbage bin. Fortunately, overall, we find only a bit of hazardous waste such as batteries, and we also do not come across illegal dumps or heaps of waste; mostly individual waste items are found.

We collect mainly plastic waste such as plastic packaging and plastic bottles, beer and soda cans, caps, paper such as parking tickets, receipts and cigarette packaging, cigarettes butts and, in this time, also face masks. When trying to estimate the origin of waste, it appears that the found waste has been either blown away from garbage bins, bags, containers and the like or intentionally littered on the spot. Green areas such as the city park, the provincial Domain Kessel-lo, the Park Abbey and the campus are generally the cleanest ones. Only the abbey of Keizersberg is an exception. We suspect that this hidden and not easily accessible green oasis serves as an ideal place where mainly groups of young people gather to ‘have fun’. As we assumed, the most waste is found in the residential and industrial areas. We see that water bodies such as the Dijle river and the canal contain waste, but we do not include them into our mapping research. Regarding the exact type of place where the waste is found, most of it is in grass, flower beds or bushes. There the waste gets easily stuck and is also not immediately visible. It seems that the city’s cleaning service does not pay too much attention to these places, and the waste pickers do not really ‘search’ for waste as we did. Hence, even if the paved streets and areas look clean, it is most likely that there is some waste hidden in grass and bushes.

In the afternoon we return to the lab to do the first analysis and measurements. We classify, count and weigh the waste. It is quite a tedious work especially after a few hours of biking , searching for, tagging and collecting all the waste. But thanks to everyone’s input and effort and a good teamwork and planning we manage this. The day ends and we go home full of impressions from exploring Leuven the way no one of us has ever done before.

By collecting waste, sorting it out and discarding it in a correct way when we did not need it anymore, we killed two birds with one stone. Besides getting data for our development plan, we also cleaned up Leuven a bit and make it nicer and safer. In terms of number this translates into:

- Total Weight of Collected Waste: 18, 565 kgs

- Total Number of Collected Waste Items: 1458 items

Since waste as such is a new topic of Living Lab, we are the pioneers who had to beat a new path and developed our plan, methodology and fieldwork very independently not having the luxury of relying and building on previous development plans. We believe we managed this challenge very well. Needless to say, there are other topics and areas of research we do not cover and which would be worth looking into. For example, it would be interesting to explore the relation between waste and the number and spatial positioning of garbage bins, to focus on specific places or institutions such as schools and the litter found in their vicinity or to try to estimate the impact of climate and weather on waste dispersal. Either way, we hope our development plan can be useful and can serve as a good starting point for not only a better and more sustainable waste management in Leuven and Belgium, but also for South Africa and the Ndumo region.

Thank you everyone for your effort, especially to all the waste groups helping us with the research and at the same time making Leuven a cleaner city! Well done!