Carbon storage, Forest Transition and the Road to Sustainability in Vietnam

By Fernanda Peixoto Silva

In Vietnam, where much of the country’s economic activity revolves around rural life and the use of land, extensive deforestation throughout the past century increased beyond precedents. As far back as 1943, nearly half of Vietnam’s once-thriving forests had already vanished. Yet, as the 20th century drew to a close, the forest cover dwindled even further, leaving only a mere 10% (Rigg, 2000). The land, which had long been the source of livelihood for many, endured the most rapid deforestation.

Nevertheless, a transformative shift is underway in Vietnam’s landscape, marked by a gradual increase in land cover. But the journey towards sustainability is far from complete, emphasizing the ongoing efforts needed to secure a more balanced and ecologically sound future.

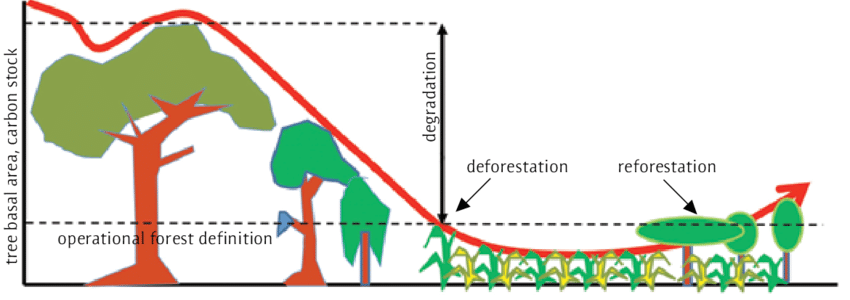

Forest transition curve + Van Noordwijk, Meine & Sunderland, Terry. (2014). Productive landscapes: what role for forests, trees and agroforestry?. ETFRN News. 56. 9-16

The call for changes

The repercussions of deforestation in Vietnam extend far beyond the loss of lush landscapes. As trees disappear, the local environment takes a hit. With fewer trees to provide shade and absorb carbon dioxide, temperatures rise, disrupting the delicate balance of ecosystems. Changes in rain patterns can lead to both more floods and more droughts. This is especially worrisome in our era, where climate change and global warming are pressing concerns.

Forests act as carbon sinks, absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in trees, vegetation, and soil. This helps mitigate the impacts of climate change. The accumulation of excess CO2 in the atmosphere traps solar heat, contributing to global warming. Halting deforestation and preventing forest degradation are key strategies in mitigating climate change.

In Vietnam, despite experiencing rapid deforestation that peaked in the 1980s, a positive shift emerged in the following decade. The 1990s witnessed a transformation in policies, contributing to an improvement in land cover and setting the stage for a more sustainable future.

The forest transition

Since the 1990s Vietnam has undergone a transformative forest transition, shifting from net deforestation to net reforestation. This shift was accompanied by an increase in forest cover, which grew steadily from 24.7% of the country’s area in 1992 to 38.2% in 2005 (Meyfroidt & Lambin, 2008). Different factors collaborated for that, changes in political, socioeconomic, and land-use processes contributed to this reforestation effort. As an example, the government implemented logging restrictions in natural forests through successive forestry policies and took the step of banning the export of raw logs (Meyfroidt & Lambin, 2009). However, fieldwork in northern Vietnam revealed numerous degraded areas, indicating land subjected to processes such as deforestation, soil erosion, or other forms of degradation. This diminishes the potential for carbon sequestration and storage, raising questions about the effectiveness of certain policies and bans.

On the other hand, ongoing reforestation efforts, especially for subsistence and fruit-bearing tree cultivation, demonstrate a positive initiative toward ecosystem restoration and sustainable land use. Planting trees for subsistence ensures local communities access essential resources like food, wood, and non-timber forest products. Fruit-bearing trees, in particular, contribute to livelihoods and biodiversity by attracting a more diverse range of wildlife and insects, besides increasing potential for carbon storage. Additionally, agroforestry systems, when trees are integrated into agricultural landscapes, were identified as contributing to the observed land use change. This approach promotes a more sustainable and resilient ecosystem by enhancing biodiversity, improving soil health, and supporting local livelihoods.

Nevertheless, the forest transition in Vietnam also saw changes in forest density, with an increasing proportion of either young, either degraded forests. These changes had varying effects on habitats, leading to altered landscape patterns. While reforestation decreased forest fragmentation in some regions, others experienced the clearing of old-growth forests and increased fragmentation. As a result, the Vietnamese landscape became fragmented, reflecting different land use and land cover patterns (Meyfroidt & Lambin, 2009).

If you are unfamiliar with the concept of “forest transition,” you might initially presume it relates to the restoration of pristine forests to their pre-deforestation state. However, the forest transition is a nuanced process. It not only involves the resurgence of forests but also a broader increase in vegetation cover. This transformation is not solely about reverting to historical conditions but can rather encompass strategic reforestation that adds substantial value for the farmers who have their livelihoods from the land.

Forest transition is a comprehensive journey with the potential to cultivate a greener, economically prosperous, and more sustainable landscape.

Fieldwork in the mountain’s region of Vietnam

In September 2023, the KU Leuven Sustainable Development MSc program embarked on a two-week fieldwork in the mountainous northern region of Vietnam. This part of the country is famous for its stunning mountain landscapes and vast rice fields. The students were divided into different groups, each assigned a specific study. I was part of the carbon storage group, and our plan was to collect and analyze data related to carbon storage and collaborate with the biodiversity group.

From a carbon storage perspective, our sampled plots reflected various land uses, with basal area as a variable to assess tree density. In practice, these measurements helped us understand the potential for carbon storage across different land uses in our study area. In the context of Vietnam, where deforestation and reforestation efforts are ongoing, it is quite important to investigate different land uses and their potential to stock carbon.

Our fieldwork in Vietnam revealed a diverse landscape, from rice paddies to agroforestry and secondary forests. Results showed that home gardens had a relatively low basal area, which means sparse tree cover, while croplands like peanut and maize fields exhibited no tree cover. Secondary forests and agroforestry systems consistently showed the highest basal area, indicating various levels of regenerating tree cover. However, these values are notably lower compared to old forests, meaning although better, still not the same as mature forests.

Interestingly, the locals demonstrated savvy forestry practices, particularly in a garden plot we studied. About 10% of the trees were high-quality wood, while the majority were lower quality but still fruitful, providing economic benefits. This intentional distribution serves as a long-term investment, generating revenue from valuable wood and commercial goods. It is a practical model showcasing the community’s adaptability and resilience in managing resources for economic stability, while reducing the occurrence of ‘less useful’ tree species for their livelihoods. It shows how communities can navigate economic challenges by thinking long-term and using resources wisely.

Ideally, a more balanced approach to tree quality and diversity would be preferable. However, in the current socioeconomic conditions, the showcased example serves as a practical model for adaptation and resilience in the face of uncertainty. It is important to note that while this scenario may be positive at a household level, it also entails lower biodiversity and carbon stocks as compared to the original natural forest.

While there have been notable improvements and some degree of community awareness and effort identified, the data reveals a relatively low carbon content in these plots, with slightly higher levels observed in agroforestry systems and secondary forests. The fieldwork unveiled a highly degraded forest condition and low carbon content, emphasizing the extensive journey ahead to enhance carbon stocks through improved land use and land cover practices in the Vietnam context.

Carbon Storage

Prior to the fieldwork, we conducted preliminary research to explore the potential carbon stock in various land uses and cover types throughout the study area. This first set of data offered the foundation for creating models that estimated the carbon present in different land uses, forming what we refer to as the “carbon pool”. These initial findings gave us insights into the potential of vegetation cover in the region while also underscoring some challenges.

The preliminary data already indicated a highly fragmented land use pattern, characterized by fewer secondary forests and an absence of mature forests. The predominant landscape comprises a mosaic of various uses for livelihoods, such as fruit gardens, maize, cassava, peanuts, bamboo, and other crops. Natural forests are undergoing transitions into cultivation and selective logging.

Following our fieldwork and soil sampling, a closer examination of the wet soil samples revealed significant insights. Interestingly, agroforestry systems and secondary forests exhibited healthier soil conditions compared to other locations we investigated. The importance lies in the role of soil in the carbon cycle, serving as a durable storage unit. Unfortunately, when forests are converted into large farms or plantations, it often degrades the soil, leading to the loss of carbon stocks. Our on-site research demonstrated that areas transformed into cropland, shrubs, and gardens have limited carbon storage, indicating that the vegetation struggles to capture and retain carbon effectively. Additionally, forests disrupted by roads or urban development may experience detrimental changes, altering the entire system and potentially resulting in carbon loss.

In essence, there is substantial work remaining in the realm of forest management, particularly in enhancing carbon sequestration and storage. This effort should also encompass other crucial factors, including livelihoods, as well as ecological and biodiversity considerations.

Challenges and Sustainable Practices

Reforestation efforts in Vietnam come with their share of challenges, including illegal logging and land-use conflicts. These obstacles pose threats to the sustainability of these vital initiatives.

Restrictive policies within Vietnam, while beneficial in partially reducing deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions within its borders, can sometimes inadvertently lead to these issues being pushed elsewhere, most notably to neighboring countries like Cambodia (Meyfroidt & Lambin, 2009). Leakage is a global problem that requires a concerted effort to address comprehensively. It is important to develop strategies that not only shift the problem but provide long-lasting and sustainable solutions, otherwise management within the boarders will not resolve the problems. Additionally, illegal logging seems to still be taking place in the study area as observed during field, indicating, once again, that law enforcements and restrictive polices might not being effective.

Nevertheless, while Vietnam’s landscape show signs of degradation, the presence of reforestation initiatives signifies a positive step toward ecological restoration and community well-being. Understanding the motivations and practices behind these reforestation efforts will be valuable for assessing the overall success and impact on the region’s sustainability. Additionally, considering the potential for carbon storage in these reforested areas can provide insights into their role in mitigating climate change and enhancing environmental resilience.

Vietnam’s case stands as a valuable example of forest transition and positive change. However, it also underscores the ongoing work required to align with sustainable forest practices and make substantial contributions to climate change mitigation. Recognizing the progress made, there remains an opportunity for further collective efforts to enhance these positive developments without undermining the achievements already accomplished.

References

Meyfroidt, P., & Lambin, E. F. (2008). Forest transition in Vietnam and its environmental impacts. Global Change Biology, 14(6), 1319-1336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01575.x.

Meyfroidt, P., & Lambin, E. F. (2008). The Causes of Reforestation in Vietnam. Land Use Policy, 25(2), 182-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.06.001.

Meyfroidt, P., & Lambin, E. F. (2009). Forest transition in Vietnam and displacement of deforestation abroad. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(38), 16139-16144. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0904942106.

Rigg, J. (2000). Review of [De Koninck, Rodolphe (1999) Deforestation in Viet Nam. Ottawa, IDRC, 101 p. (ISBN 0-88936-869-4)]. Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 44(121), 97–98. https://doi.org/10.7202/022889ar.

Van Noordwijk, Meine & Sunderland, Terry. (2014). Productive landscapes: what role for forests, trees and agroforestry?. ETFRN News. 56. 9-16.]

![Forest transition in Vietnam by Hubert Claes © SUSDEV]](https://susdev.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/stream-scaled.jpg)