By Madelein Victor, Paulina Ocampo, Sahil Nair, Catherine Achoke, Saga Henriksdotter

Students don’t necessarily spend their time working in labs and classrooms all day. Five daring, adventurous, and courageous students went out into the untamable wilderness, meticulously preserved nature, in their quest for knowledge (and macroinvertebrates), wearing their chest waders instead of Nike sneakers. Though a bit scared of hidden crocodiles, we bravely stepped into the waters armed with nets and buckets.

A lot of lessons and quite a bit of fish information are learned in those two weeks in Ndumo Game Reserve. These students may have come from different backgrounds but worked together as the Biotic Water team conducting fieldwork in the Ndumo Game Reserve and its surrounding areas. We had the privilege to return to South Africa after the Living Lab was not conducted there for two years because of the COVID pandemic. It was exciting to see what changes have occurred over the past years, especially because the drought had ended, and new waterways have been flooded. We’re still working on our final development plans, but we’ve found a lot more fish species and macroinvertebrate families than the previous years – which is a pretty exciting finding for all of us. We all have something to say about our experience and a few tips for the next batch.

Madelein

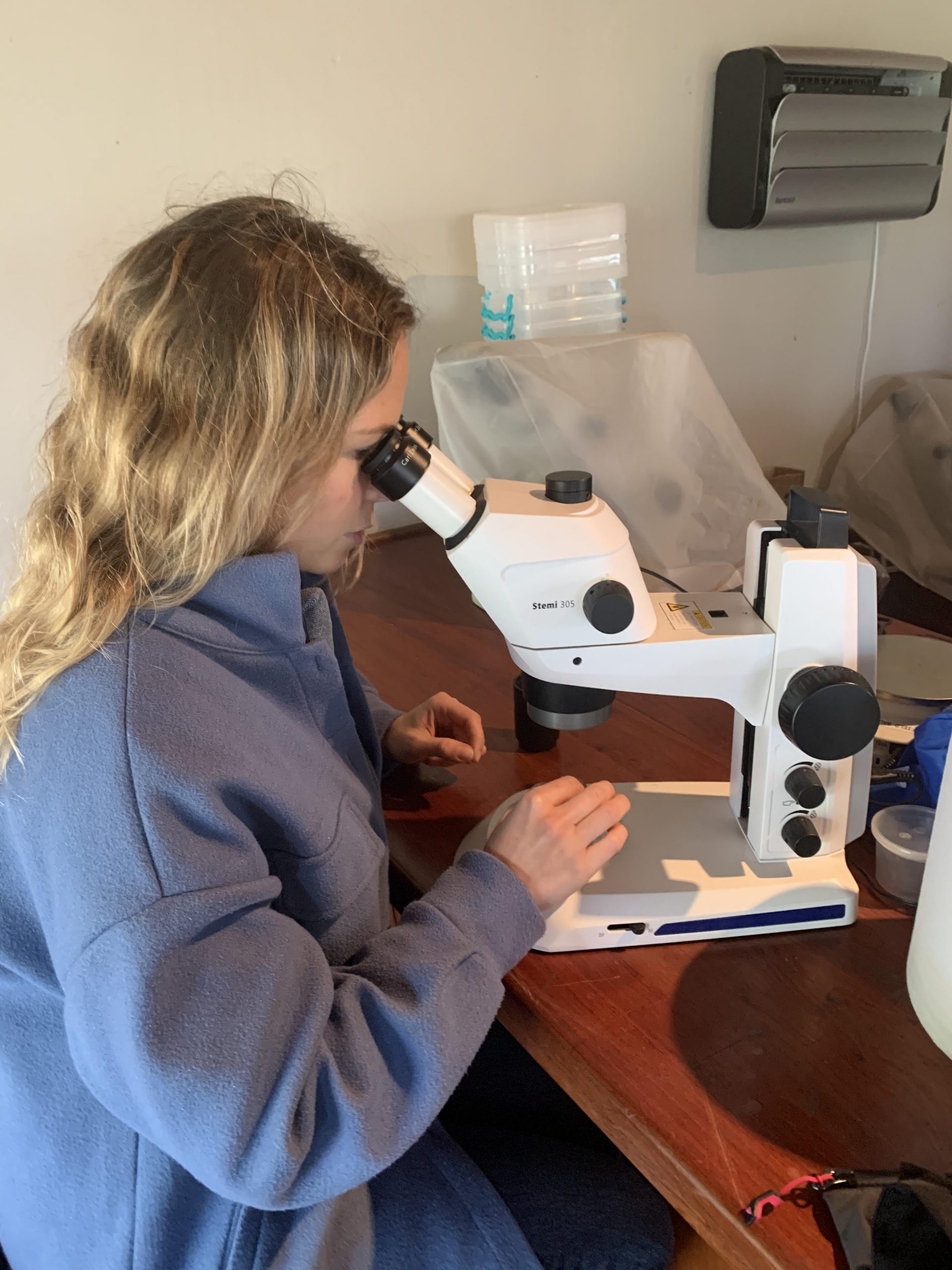

This experience taught me so much about biodiversity, different cultures and development overall. Additionally, even I was impressed by my own social skills and energy levels. I joined the water team because I previously worked with the Water Research Group of NWU, the local university that helped us a lot, and I wanted to work with them again, trampling through the murky waters, searching for mysterious critters. Funny enough, everybody from different groups liked our fieldwork so much, some of them even considered moving to our team. I liked helping others understand what we were doing and what we were researching and coming from South Africa this felt like I never left home. I would like to thank everybody that helped us and identified the macro-invertebrates because I know without you guys, we would’ve still sat at the microscope trying to identify dragonfly larvae even with the terrible case of loadshedding. My advice for people going into the next Living Lab, be 100% bold and try new experiences, this will definitely tickle your inner Saffer.

Paulina

As someone with a background in Anthropology, I was a little hesitant to join the biotic team. What would I be able to contribute? I studied people, not water insects. But over the days of Living Lab, I learned a lot about identifying fish and macroinvertebrates and what they can tell us about water quality. I enjoyed my time in the waders; it was fun to investigate the different micro habitats for critters. It was a joy to see all the shrimp and insects bouncing around my net after a successful scoop. The post-field work in the “lab” was quite tough – we would work without power because of load shedding and until it was late to identify everything, all of this in the common room with the rest of the cohort. It can get tiring and uncomfortable, especially for introverts (say bye to your me time for a bit!) and people who aren’t used to camping (hello insects, cold showers, and messy tents), but that’s part of the experience.

Whether you decide to be a field conservationist or maybe to study graphs and numbers behind a desk, it’s a reminder that a whole lot of effort is put into making projects happen on ground. It got easier as time went on because everyone wanted to help, which was something I didn’t expect and now a core memory of Living Lab. That, and I don’t think I’ll ever forget what an Odonata larvae looks like. My tip for the next batch is don’t be scared to ask for help from your supervisors and classmates and on the practical side, to bring your own extension cord. Good luck!

Catherine

I have always loved adventure, and there was none other more exciting and fulfilling than the Living Lab. This year we travelled to Ndumo Game Reserve, Eastern South Africa. The two weeks we camped in the reserve was very special!

Prior to setting off, the impression I got was that there wasn’t going to be too much interaction between the different groups. But as it turned out, the biotic group, particularly the fish and invertebrate group, my assigned topic, had so much to learn from both the Ecology and Space and society. As we began our data collection, mornings were extremely beautiful, waking up in our tents to chirping birds and astonishing sunrises. As we drove through the enormous game reserve, we tranversed diverse terrestrial ecosystems, and emerged into yet stunning wildlife, rivers and pans. Of course, we couldn’t resist getting into the water to get our samples. We were pleased to catch different species of fishes and a descent sample of macroinvertebrates, that we would later identify and put them into families at the camping site.

We also travelled all over the Ndumo region, interacting with the local communities, understanding their perspectives with regard to conservation, climate change and development. When the day of our final presentation of our work reached, I had reflections of how Living Lab was about testing ourselves, having fun together and acquiring the best possible data for our development plans, it is a wonderful set up to reimagine learning and transforming education.

Sahil

I was really excited to join the water group. The idea of going into the pans and rivers in a nature reserve and being outdoors was really appealing for me. However, things got very technical very quickly and a bit overwhelming when the fish and macroinvertebrate field work started. There were so many fishs and macro invertebrate species! Being from an economics background, I remember thinking that it is impossible for me to ever identify any species correctly. However, like the hatching of fairy shrimps from the sediments of dry pans, we just needed to spend a few days in the water (and in front of the microscope) to grow our biotic knowledge!

Overall, I learned a lot from the living lab, and not only about the biotic aspects of freshwater ecology but how abiotic elements and invasive species all are connected to each other. It was also good to see that all the other groups taking keen interest in our sub-group. After a whole day of physically demanding field work, they stayed up late to identify the macroinvertebrates. Even during load sharing, people used the microscope with torch lights and finished the job! The data is yet to be fully analyzed, and we will try our best to do justice to all the hard work put in by the NWU students, staff, profs and our fellow batch mates.

Saga

There is something special coming from social sciences and suddenly finding yourself in the Pongolo river basin trying to fish shrimps with crocodiles just a few meters away. That switch was of course huge for me as a person to experience as it was a chance to challenge my fears and actively dare new things. But I am not studying Sustainable Development to challenge my fears. I started this program with the aim of gaining knowledge and understanding to make me a better contributor to our common goal of halting the climate and environmental crisis. The question I struggled with before arriving in Ndumo was therefore not how many cool animals I would see, but how this fieldwork would give me important insights for being able to be a good sustainability practitioner.

I do not yet, and will probably not have in a very long time, a clear answer to how this fieldtrip contributed to the aims which brought me to start this program. But already the first days after coming back from waders-style in South Africa to suit-style at the European Parliament where I have my internship, I realized that the fieldtrip had given me a lot of insights that I would not have been able to gain elsewhere. When I read policy papers on carbon sinks, I could now relate it to how we measured trees carbon density in Ndumo. When I met Elizabeth Wathuti who shared the testimonies of victims of climate change at the Parliament, I could now grasp what she was speaking about as I had talked with people impacted by the drought in Ndumo. It might not be the exact knowledge on how to measure a catfish that I will carry with me for life, but rather how the research conducted on the very smallest level is connected to big global patterns and decisions, and how greatly important that research is.